A UK-led team of scientists is rolling out a project to monitor every land volcano on Earth from space.

Two satellites will routinely map the planet's surface, looking for signs that might hint at a future eruption.

They will watch for changes in the shape of the ground below them, enabling scientists to issue an early alert if a volcano appears restless.

Some 1,500 volcanoes worldwide are thought to be potentially active, but only a few dozen are heavily monitored.

One of these is Mount Etna where, last month, a BBC crew was caught up in a volcanic blast while filming a report on the new satellite project.

When we visited Etna's slopes last month, volcanologist Boris Behncke from Italy's National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology (INGV) showed us one of its monitoring stations. "We have about 40 GPS stations, more than 60 seismic stations, and we have magnetometers, gravity meters, cameras, thermal cameras, radar instruments, gas metres. Whatever can be measured, we are measuring."

The data feeds back into the INGV's hi-tech control room in nearby Catania. It is staffed 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Dr Giuseppe Puglisi explained: "Collecting this data enables us to detect any changes in the volcano's physical or chemical status. For example: changes in topography, changes in the temperature of the rocks, or on the stress of the crust, or changes in the composition of its minerals or gases, etc. These are all important to identify whether an eruption looks possible."

However, very few volcanoes around the world receive this level of scientific attention. Instruments are expensive and it takes many scientists to keep track of all of the data that pours back. Dr Behncke said: "Etna is certainly one of the most intensely monitored volcanoes on Earth - maybe the most monitored volcano on Earth. But obviously there are many other volcanoes, and many dangerous volcanoes, especially in poorer countries, where monitoring is much more rudimentary or completely absent."

The satellite project could make a big difference to these places, but it will also be useful for Mount Etna too. "The advantage lies in the ability to monitor wide areas of the volcano at once," said Dr Puglisi.

Before a volcano erupts, magma rises from deep beneath the Earth, causing the ground above to swell. It usually starts as a small movement on the flank of a volcano or in its caldera (crater). It may be barely noticeable to the eye, but it can be seen from space.

Regular satellite data recording this change will be processed automatically and an alert issued for scientists to follow up. A "red flag" would not mean an eruption is a given, but it ought to ensure those communities that live in the shadow of a volcano are not caught unawares if the situation deteriorates.

"It's the volcanoes that are least monitored where this will have most impact. If people can be alerted ahead of time, it could save many lives," said Prof Andy Hooper.

The Leeds University geophysicist is part of the Centre for Observation and Modelling of Earthquakes, Volcanoes and Tectonics.

COMET has conducted trials of the new satellite-monitoring system in Iceland and is now running it in prototype form across Europe and parts of Asia.

The plan next is to extend the automated detection of ground deformation to Africa and Central and South America. These regions have some very big explosive volcanoes that are covered only by limited ground surveys.

"In Ecuador, for example, there are roughly 80 volcanoes, four of which are erupting at any one time, and a very small staff to keep an eye on it all. So, they will be grateful of the assistance," said COMET team-member Dr Juliet Biggs from Bristol University.

There is a certain irony in making a report about forecasting eruptions and then getting caught up in a volcanic blast. When we filmed in Sicily, the volcano was in one of its fits of activity, and we had gone to see a lava flow that had appeared overnight. But a few minutes after arriving, the lava started to explode. Blisteringly hot rocks were shot high into the air, which then began to rain down on us and dozens of tourists.

We ran for our lives, and somehow escaped only with minor injuries. The event we witnessed is known as a phreatic explosion. Its cause was hot lava mixing with icy meltwater which had pooled underneath the flow, causing pressure to build rapidly. In 2013, scientists studying the Tolbachik volcano in Russia saw a similar explosion as lava advanced over very thick snow. Luckily, they too were not hurt. But it is unlikely that these incidents can be easily forecast - either from the ground using instruments or from space.

Dr Puglisi said: "It's not very easy to predict phreatic explosions. "The mechanism occurs very fast. The explosion is caused by the almost instantaneous evaporation of vapour, usually in small areas. These phenomena are usually relatively shallow and, in some cases, practically at the surface. So this doesn't produce significant changes detected by monitoring systems. And in space, the resolution is not suitable to detect such phenomena."

There is relatively little video footage of phreatic explosions and so the BBC film, captured by camerawoman Rachel Price, will be of interest to scientists as they try to learn more about these incidents.

Key to the space monitoring project is the capability offered by the European Unions's new Sentinel-1 radar satellites.

This pair of platforms repeatedly and frequently image the entire land surface of the globe, throwing their data to Earth using a high-speed laser link.

By comparing a sequence of Sentinel pictures, in a technique known as interferometry, COMET's computing facility can track really quite small changes in the behaviour of a volcano, on the order of just millimetres (the movements that might be most concerning would in all probability be much larger and even easier to sense).

"Satellite radar interferometry as a technique has been around for over 20 years now. But it's really only been used in the past retroactively, to try to understand what happened at a volcano after it erupted," explained Prof Hooper.

"The point here is to try to see things in advance, to move to more of a forecasting mode; and to have all the data available in near-real-time."

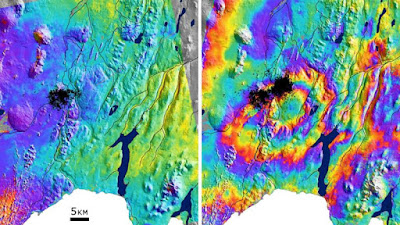

- The featured pictures are of a volcanic region in the north of Iceland

- Satellites sense ground movement as magma rises up from deep in the Earth

- Surface bulging becomes apparent by comparing images taken in a sequence

- The left picture shows a time just as activity is about to get under way

- On the right, the ground is lifting and quakes are increasing (black dots)

- The amount of deformation is represented by coloured "fringes", or contours

- Each fringe cycle (e.g. purple to purple) denotes 3cm of movement upwards

- Computers will automatically recognise such behaviour at all volcanoes

The 1,500 figure is the number of land volcanoes that are known to have erupted at some point in the last 12,000 years (more volcanoes exist under the sea but cannot be seen from space). Many will appear long dormant, but every two years or so there is an event on a volcano that has no previous mention in the written records of having erupted. And in some parts of Africa, these records can start as recently as the 19th Century.

One of the big research questions for scientists is working out if and when a change in the shape of a volcano will lead to an eruption.

It can be a long time between the two, perhaps years. But the statistics suggest it is four times more likely that a volcano that deforms will erupt than one that has not changed its shape.

"It's not a case that if you see deformation you should evacuate people tomorrow," said Dr Biggs. "But what we desperately need is more examples, and that is where the Sentinel system is really important because we will be able to track all these volcanoes in a routine and systematic fashion."

The aim is to have the satellite data on all 1,500 volcanoes being gathered and processed by the end of 2017.

No comments:

Post a Comment